May 24, 2017

LTJG Blair Delean

NOAA Corps Officer

Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS) have recently become a major tool for studying wildlife. UAS allow scientist to capture aerial imagery of marine life in remote locations with more flight flexibility, and at lower cost than most manned aircraft missions. As a Lieutenant (Junior Grade; LTJG) in the NOAA’s Commissioned Officer Corps (called “NOAA Corps”) and recently designated UAS Pilot in Command at the Alaska Fisheries Science Center, I will be traveling to the Aleutian Islands this summer to study Steller sea lions using UAS. This is the same research cruise that members of the Steller Watch Project research team will be a part of to collect remote camera images.

The NOAA Corps today consists of a team of professionals trained in various scientific disciplines who operate NOAA’s ships, aircraft (like the annual Steller sea lion aerial survey), conduct diving operations, manage research projects, and serve in staff positions throughout NOAA offices.

The NOAA Corps is one of the Nation’s seven uniformed services comprised of 321 officers who serve throughout NOAA’s line and staff offices to support virtually all of the agency’s programs and missions. TheNOAA Corps traces its roots to the former U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, which originated in 1807 under President Thomas Jefferson.

The NOAA Corps today consists of a team of professionals trained in various scientific disciplines who operate NOAA’s ships, aircraft (like the annual Steller sea lion aerial survey), conduct diving operations, manage research projects, and serve in staff positions throughout NOAA offices. NOAA Corps Officers are primarily stationed in the continental United States; however, there are some positions located as remotely as Antarctica, Hawaii, and the Samoan Islands in the South Pacific.

Currently, officers operate 16 research vessels which are strategically stationed at various locations around the country. These places include Norfolk, San Diego, Gulf of Mexico, Pacific Northwest, and Honolulu which is where I was last stationed before my assignment to the Alaska Fisheries Science Center in Seattle. The ships are crewed by both NOAA Corps Officers and civilian wage mariners to serve NOAA’s fisheries, hydrographic, or oceanographic missions. The aviation component is comprised of both manned and unmanned aircraft systems operated by Corps officers stationed at the Aircraft Operations Center in Florida.

My path to becoming a UAS pilot for NOAA began following my graduation from the Basic Officer Training Class (BOTC) at the United States Coast Guard Academy in the spring of 2014. I was then assigned to the NOAA Ship Oscar Elton Sette in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. While on the Sette my primary duty was to drive the ship, manage scientific operations, and to serve as the Navigation Officer. Some of my other responsibilities included being the environmental compliance, dive, and property officer. We sailed the main Hawaiian Islands and beyond through the remote Northwest Hawaiian Islands which extend 1,200 miles from Kauai.

In the fall of 2016, following my tour on the Sette, I was assigned to the Marine Mammal Laboratory at the Alaska Fisheries Science Center in Seattle, WA. This is when I became involved in UAS operations. I completed the Federal Aviation Administration’s remote pilot exam, followed by the UAS manufacturer training, and then received my UAS Pilot in Command designation from NOAA. Since obtaining my PIC designation I have completed a few practice flights with the scientist UAS team here in Seattle in preparation for the upcoming Steller sea lion field research cruise in the Aleutian Islands this summer. I’m looking forward to my first trip to Alaska—it will be a big change from Hawaii.

I graduated from the University of Maryland, College Park with a degree in Environmental Science and Policy, Marine and Coastal Management (2010). While in college I also played baseball for the Terps, and completed an internship at the Cooperative Oxford Laboratory in Oxford, Maryland. Following graduation (prior to the NOAA Corps) I worked as a contracted Special Investigator for the Office of Personnel Management, and as in intern at the White House Council for Environmental Quality in Washington, D.C.

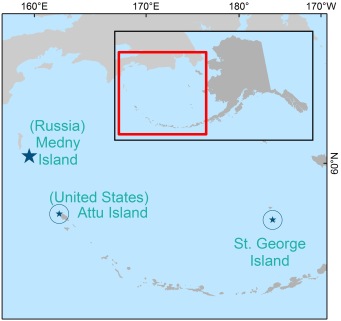

This fella stayed pretty close to home, Medny Island, during his younger years. The last time he was seen on Medny was in the summer of 2014. He was then seen almost 900 miles away on St. George Island (part of the Pribilof Islands in the eastern Bering Sea, Alaska) on March 19, 2015. That’s a long ways away! Many of you have reported seeing him on Cape Wrangell on Attu Island on images taken during the summer of 2015. He had a bit of a ‘walk-about’ and ended up returning to Medny Island during the summer of 2016. I wonder if he’s getting ready to start putting up a fight for a breeding territory or if we’ll see him again back on Cape Wrangell again soon?

This fella stayed pretty close to home, Medny Island, during his younger years. The last time he was seen on Medny was in the summer of 2014. He was then seen almost 900 miles away on St. George Island (part of the Pribilof Islands in the eastern Bering Sea, Alaska) on March 19, 2015. That’s a long ways away! Many of you have reported seeing him on Cape Wrangell on Attu Island on images taken during the summer of 2015. He had a bit of a ‘walk-about’ and ended up returning to Medny Island during the summer of 2016. I wonder if he’s getting ready to start putting up a fight for a breeding territory or if we’ll see him again back on Cape Wrangell again soon?

From the remote camera images, ~22 is seen very regularly at Cape Wrangell. The last time he was seen with his mom and suckling was way back in October 2012 so he was likely weaned shortly after. This is earlier than what we observed for

From the remote camera images, ~22 is seen very regularly at Cape Wrangell. The last time he was seen with his mom and suckling was way back in October 2012 so he was likely weaned shortly after. This is earlier than what we observed for

You must be logged in to post a comment.